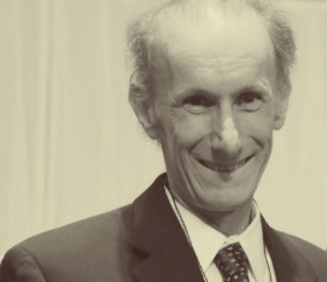

Foco Económico recuerda a Julio Rotemberg con un muro de memorias. Escribe una nota introductoria Pablo Kurlat y siguen reflexiones y recuerdos de quienes trataron a Julio como amigos, o como colegas, o como discípulos. Entre ellos, Iván Werning, Anil Kashyap, Jim Poterba, Olivier Blanchard, Martin Rotemberg y Michael Woodford. Invitamos a los lectores a compartir alguna reflexión o anécdota personal en los comentarios.

Mi tío Julio Rotemberg, quien murió la semana pasada, fue uno de los más grandes economistas argentinos que ha habido. Yo no lo tenía tan claro hasta que llegué a la Di Tella. Hugo Hopenhayn, uno de mis profes, se había enterado que éramos parientes y me preguntó si sabía lo importante que era mi tío. “Es profesor en Harvard, así que calculo que…” empecé a contestar yo. “No, es al revés”, me corrigió Hugo: “Julio le da prestigio a Harvard”.

Era un tipo muy inusual. En esta época en que todos nos especializamos en temas muy estrechos, a él le interesaba todo. Pasó buena parte de su carrera pensando en macroeconomía, en los así llamados modelos Neo-Keynesianos. Pero también se dedicó a pensar en los orígenes de las normas sociales, en cómo funciona el altruismo y mil cosas más. Respetaba, cosa poco común entre economistas, a otras ciencias sociales: hablaba (¡a propósito!) con historiadores, psicólogos, sociólogos y antropólogos, y conocía sus maneras de pensar. Por varios años dio clases de marketing.

En lo personal, tuve la suerte de tenerlo cerca y verlo cada dos o tres semanas durante los años que estuve haciendo el doctorado. Creo que le gustaba hablar conmigo, y con las generaciones más jóvenes en general.

Junto con el equipo de Foco Económico les pedimos a algunos de quienes lo conocieron que compartan sus recuerdos sobre él. Acá los tienen.

Por mi parte, lo voy a extrañar.

Pablo Kurlat

Stanford University

Gran pérdida la de Julio, desde el punto de vista profesional y humano. Mis condolencias para su familia y amigos más cercanos.

Desde temprano y desde lejos, fui un admirador incondicional de su investigación. Sus trabajos se destacan por tener una rara mezcla de creatividad y relevancia. Era fácilmente uno de los macroeconomistas más influyentes de su generación, pero me da la impresión de que a Julio no le importaba mucho llevar un rol de líder en un nicho acotado, y en cambio prefería dejar que su gran curiosidad lo lleve deambulando a otros temas fuera de ese ámbito.

Cuando llegué a MIT, Julio se había mudado hace varios años a Harvard Business School, pero con cualquiera que hablaba lo recordaban y alababan de sobremanera. Pude interactuar con él en Cambridge en algunas ocasiones. Pocas, pero muy valiosas. Cuando daba una charla en MIT uno veía lo rápido y profundo que trabajaba su mente, además del respeto que le tenían todos. Pero lo que más se destacó para mí es su curiosidad intelectual sin apegos y sin egos. Una pequeña anécdota que ilustra esto. Después de un seminario interesantísimo que dictó en MIT, le escribí para señalarle una conexión que yo veía entre su paper y un viejo paper poco conocido de Ostroy y Starr (1974). De más esta decir que esta conexión no invalidaba que Julio tuviera una contribución, pero vale acotar también que este tipo de comunicación puede ser delicada y no son siempre bien recibidas entre académicos—es muy común y humano no recibir respuesta o recibir como respuesta una reacción algo defensiva que minimiza la relación con lo anterior y resalta la originalidad de la idea propia. La reacción de Julio fue todo lo contrario: con muchísima curiosidad estudió el paper, discutió conmigo la conexión en varias idas y vueltas, y abrazó la conexión entre las ideas con gran ecuanimidad. (La versión final de su paper esta acá.) Le importaba mucho más discutir ideas y llegar al fondo de la cuestión, sin perderse en las mezquindades que son moneda común. En su momento, como joven economista intentando seguir sus pasos, para mí fue una gran ejemplo. Un gran erudito. Classy como nadie, como se dice por acá. Lo vamos a extrañar.

Iván Werning

MIT

I was lucky enough to meet Julio over 30 years ago when I was a graduate student and he was a faculty member at the Sloan School of Management. Julio was exceptional (even relative to all of the talented economists at MIT at the time) in two respects. First, he was incredibly curious. He would talk about any issue in economics for as long as you like. I found my dissertation topic in the course of a conversation with and I am sure so did many others. He delighted in debating ideas and would provoke you to think about a topic from all directions. Second, he was incredibly creative. He felt completely free to attack problem in a way that no one else ever had. Sometimes the results were crazy, but often they were fantastic. It is no accident that he made foundational contributions in a variety of areas.

Besides his contributions as a scholar, he was incredibly humble and modest. He set a great example for students and colleagues about how to behave with class and dignity. When word got around that he was sick, many of his friends asked him to allow us to hold a conference to honor him. He resisted not wanting to be the center of attention. It is our loss that we never convened.

Anil Kashyap

Chicago Booth School of Business

Julio was a scholar of remarkable breadth and creativity. His boundless curiosity, coupled with his analytical insight, led to important contributions in many realms of economics. He and his frequent co-author, Michael Woodford of Columbia University, created modelling tools that most central banks rely on when evaluating monetary policy. He was keen student of the way firms adjust their prices, how their pricing varies over the business cycle, and of the implications of price-setting behavior for the design of fiscal and monetary policy. His research went far beyond macroeconomics, however: he explored topics in business strategy, marketing, and the determination of customer sentiment. Julio opened new paths, and many others have extended his work. He leaves an extraordinary scientific legacy.

Jim Poterba

MIT

I miss Julio. I have missed him since he left MIT for HBS in the mid-1990s.

We were colleagues for more than a decade. Our nearly daily discussions were exciting and fun. Julio nearly always had a different angle. This was not difference for the sake of difference or for the sake of provocation. It was relevant difference, making for a richer discussion.

This was very much true of his research in general. I think it is unfair to characterize Julio just as a New Keynesian, or even just as a macroeconomist. It is true that he made important contributions there, but his research always had a wider scope, be it on variations in markups, fairness in pricing, altruism in wage setting, just to take a few of his papers from the last 10 years. Compared to the dryness of the New Keynesian model, Julio’s vision was much more complex, and much richer. This, we shall all miss.

There was something else about Julio that was very special. His kindness, and his smile. (Jordi Gali told me that Julio was the only economist he knows who was always smiling.) In a profession where egos sometimes run wild, his was nowhere to be seen. He listened, he enjoyed, he made you feel smarter, and he never made you feel bad. This I shall miss even more.

Olivier Blanchard

MIT & Peterson Institute for International Economics

En mi último año de la universidad, Julio fue invitado a dar un seminario sobre uno de su papers. Mis profesores estaban felices – fui a una universidad pequeña y en las montañas, donde no vienen mucho los profesores de Harvard. Yo también estaba feliz – fue una oportunidad para que mis amigos pudieran conocer mi padre brillante. Muchos de mis amigos -la mayoría de los cuales eran estudiantes de economía- fueron a su charla, entusiasmados por comprender finalmente de qué se trata la investigación de economía.

Al cabo de 15 minutos, Julio se había quedado sin letras griegas libres, y durante el resto de la charla creo que uso todas las letras y símbolos de todos los alfabetos conocidos. Es cierto que Julio era un maestro brillante para MBAs, pero no tuvo la capacidad de orientar sus ideas a los estudiantes jóvenes.

Una explicación podría ser que Julio no se preparó. Que tomó sus slides normales, sin cambiarlos. Pero en este caso sé que no es cierto, por dos razones. La primera es la razón directa – lo vi trabajar en su presentación y le oí practicando para hacer la charla comprensible (siempre me he preguntado qué jeroglíficos debía haber usado en su charla académica normal).

La segunda razón es que Julio es simplemente increíblemente altruista. Estudió cómo el altruismo afecta el comportamiento de las empresas, los votantes y los vecinos. Creo que se encontró con esa agenda de investigación debido a cuánto cuidaba de los demás. Su paciencia, cuidado y dedicación fueron impresionantes. Siempre ha tenido tiempo de ayudar. Estoy en la rara posición de estar en la misma profesión de mi papá, y aunque no hace falta decir que él es mi modelo profesional, no es sólo porque sus ideas era innovadores e importantes (creo – como no conozco todas las letras griegas, no llego entender todos sus papers). Es porque siempre dio comentarios picantes pero amables en seminarios, habló sobre los asuntos económicos importantes, y generalmente se esforzó por mejorar la vida de otros. Incluso en los últimos días, siempre quería discutir ideas con otros. Lo que le dio energía fue aprendizaje y el debate. Aprecio todos mis recuerdos de él, y realmente lo extraño.

Martin Rotemberg

NYU

I had the pleasure of knowing Julio for more than thirty years, and of collaborating with him on a series of projects, through which we became close friends. This has arguably been the most productive phase of my career, and it has certainly been the part I most enjoyed.

I first met Julio at macroeconomics conferences organized by the NBER, in the mid-1980s. I got to know him better, and began working closely with him, when I spent a semester as a visiting faculty member at MIT in 1988. The focus of our earliest collaboration was the role of imperfect competition, especially in product markets, in explaining fluctuations in economic activity. This is a topic that I had become interested in as a result of discussions with Mark Bils, with whom I taught macroeconomics at the Chicago Graduate School of Business. Julio instead was a macroeconomist with a strong sideline in industrial organization, who had in particular done important work with Garth Saloner, modeling collusion among oligopolists. Julio and I found a common interest in this topic, and analyzed macroeconomic implications of the Rotemberg-Saloner model of collusion in our paper “Oligopolistic Pricing and the Effects of Aggregate Demand on Economic Activity,” published in the centennial issue of the JPE in 1992. This paper was an important step toward what were eventually to be known as New Keynesian DSGE models, as it showed that use of DSGE methodology did not require one to assume competitive markets or to equate equilibrium with the solution to a planning problem. It also introduced the method of matching the predictions of a quantitative DSGE model with the estimated impulse responses to an identified disturbance obtained from a relatively atheoretical “structural VAR” model of macro time series.

We published a number of papers on the evidence for and macroeconomic consequences of variations in markups over the business cycle, and considered the support for a variety of possible theoretical models of endogenous variations in markups. While our first papers on the topic compared alternative purely real models, we were also aware that price stickiness was one possible reason for counter-cyclical markups to be observed; Julio had in fact been one of the first to work on optimizing models with sticky prices, in his dissertation research in the early 1980s. Over time our interest in the hypothesis of sticky prices grew, mainly because of a desire to be able to use our models to analyze the effects of monetary policy. This resulted in our developing a quantitative version of what is now widely known as the textbook New Keynesian DSGE model, first estimated and applied to monetary policy questions in our paper “An Optimization-Based Econometric Framework for the Evaluation of Monetary Policy” for the NBER Macroeconomics Annual in 1997.

It is difficult to imagine that my work would have taken this direction without the good fortune to have worked with Julio on the development of these ideas, through many discussions over the course of more than a decade. Before our collaboration started, I was already quite interested in the structure of dynamic general-equilibrium models of macroeconomic phenomena, and had a reasonably good command of monetary theory; but Julio was much stronger at empirical work, and also knew more about models of imperfectly competitive markets. He also had a remarkable talent for synthesizing evidence from a variety of sources in order to make a case for particular economic mechanisms, and was notably versatile in the theoretical ideas that he could draw upon in seeking to model such mechanisms. Above all, his constant good humor throughout the many years of uncertainty about how our work would work out or be received was indispensable in making it possible to carry on with what in those days was considered a relatively quixotic program of research, for which neither real business cycle theorists nor old-fashioned Keynesian economists saw much point.

Throughout his career, Julio’s interests remained wide-ranging, and in his last decade he worked mainly on topics outside of macroeconomics. An important theme of his late work was the integration of psychological insights into economic modeling, a topic that we discussed a lot without his succeeding in drawing me into any of those projects. Recently I have begun working on topics on the boundary between psychology and economics myself, and would have liked to share this adventure with Julio; but the decline in his health meant that I had caught up to him too late for that to be possible. It is hard to guess what further developments in economics we may have lost because of Julio’s untimely passing. I am certain that my own life and work will both be much poorer without access to his wisdom and support.

Michael Woodford

Columbia University