If it can happen in Santiago, it could happen anywhere. That is the uncomfortable message that the rest of the world should take from the sudden breakdown of civil order in Chile, and unfortunately it is correct.

The riots and vandalism of the last few days, which have sparked a state of emergency, a military response, and even a declaration by Chile’s president that the country is at war, have come in Latin America’s stablest and most prosperous nation. It had the longest uninterrupted democracy on the continent before the coup that installed Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship in 1973, and it has enjoyed uninterrupted democracy since his regime’s peaceful fall in 1990.

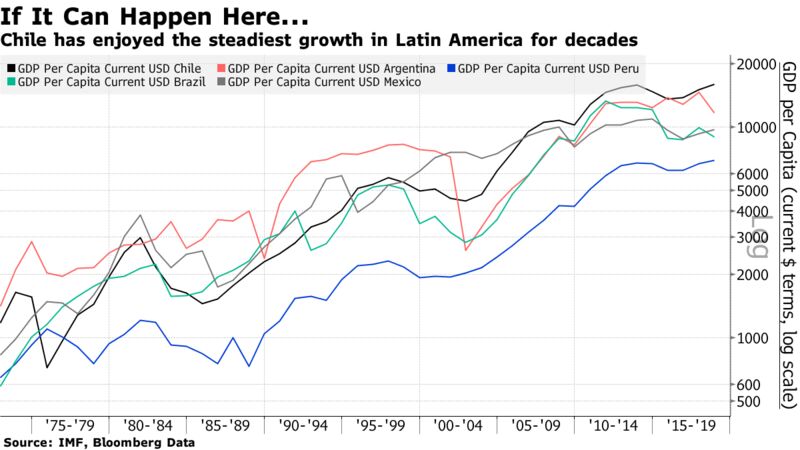

Meanwhile, globalization allowed Chile to benefit from its huge supplies of copper. In relative terms, its success is undeniable. In 1975, just after Pinochet had taken over power, Chilean gross domestic product per capita lagged Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and even its neighor Peru. Now, it has more wealth per capita than any of them. It has avoided the crises that bedeviled the rest of the region.

The fact that Chileans have revolted against the cost of living, then, is alarming, and suggests a similar situation could more easily happen in the rest of the developing world. Many assumed that insurrections like this would follow hard on the heels of the Great Recession; instead that moment seems to have been delayed amid a decade of slow recovery, but also deepening inequality. Only now is it upon us, with television pictures of protests in Lebanon and elsewhere only amplifying the message from Chile.

If Chile seems an unlikely flash point, why the blowup there? There are, I think, four critical reasons. Taken together, they offer a troubling template for other potential hot spots.

The first is inequality. The Chicago Boys’ agenda delivered reasonably strong and stable aggregate growth, but Chile remains one of the most unequal countries on earth. It ranks as one of the leaders in inequality among members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and, according to the World Bank, remains more unequal than either of its very different neighbors, Argentina and Peru. People are far angrier about a rising cost of living if it comes with a sense of injustice.

Second, the catalyst was a proposal to raise public transport fares and energy bills. There is ample evidence from across the world that these will incite rebellion like nothing else — a point that those who hope to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions via a carbon tax should bear in mind. The violent protests of the Gilets Jaunes in France were over higher gasoline taxes, which were seen as penalizing car-dependent people in the provinces while favoring metropolitan elites. Mexico in 2017 saw riots and protests against what was known as the “gasolinazo,” a 20% rise in fuel prices that was a part of the government’s partial privatization of Pemex, the monopoly state oil company. Last year, Brazil was rocked by protests and a strike by truck drivers in response to fuel shortages and a sharp increase in the price of diesel.

Third, Chile lacks a populist movement, or a canny populist caudillo politician. Such a figure might have been able to use public anger for their own purposes, but would also have had a better chance to control it. For example, Mexico’s left-wing populist president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador frequently led public protests, but successfully persuaded his followers not to resort to violence. In Chile, where conventional politics lacks a party or a personality to channel their grievances, protesters have resorted to self-destructive vandalism. Which is to say, while charismatic Latin American populists understandably tend to make western leaders nervous, Chile shows that they can perform a vital function.

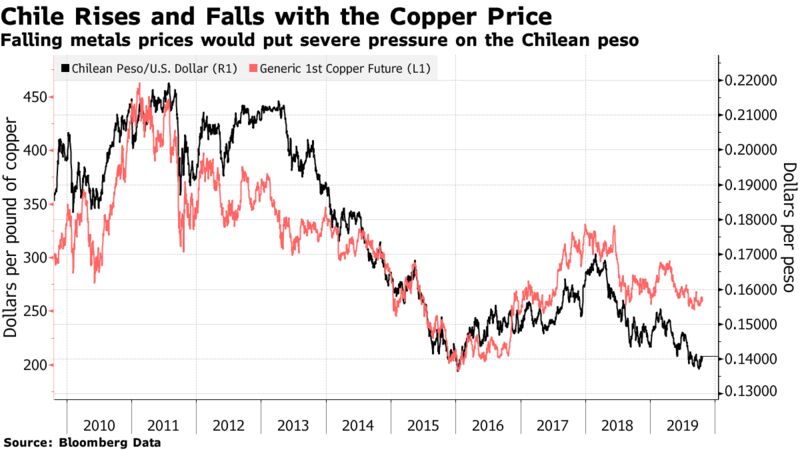

Finally, Chile’s dependence on commodities, particularly copper, set it up to suffer severe collateral damage from China’s economic deceleration, and from the U.S.-China trade war. Chile is greatly dependent on its exports of copper, whose price is in turn dependent on the health of the Chinese economy. With Chinese growth slowing to 6%, the slowest in three decades, copper prices are under pressure again. That has led very directly to pressure for the Chilean peso:

A weakening currency makes it harder for the Chilean government to balance its books. Chile’s leaders need to answer questions as to why they have not managed to diversify their economy away from a reliance on metals. But the country is far from alone. Several other emerging countries are similarly exposed to metals prices, including Brazil.

U.S. President Donald Trump has said that he expects to sign a trade deal with China next month — at a summit in Santiago, of all places. There could scarcely be a more appropriate venue. If Trump or his counterpart Xi Jinping of China is in any doubt as to the damage their conflict could wreak on the rest of the world, they might want to take the chance to look around while there.