This is based on the Minneapolis Fed Working Paper 723, “Sovereign Default: The Role of Expectations”, by Joao Luiz Ayres, Gaston Navarro, Juan Pablo Nicolini and Pedro Teles.

Bonds issued by sovereign governments are special since there is no collateral posed and there are no international courts that can make the contracts enforceable. As a result, the interest rates charged on those bonds depend on market expectations regarding the ability and the willingness of future governments of those countries to repay the debt. Thus, interest rates charged on sovereign bonds are typically higher than risk free bonds, say, the US or German ones. This difference is called the default premium or the default spread.

Naturally, the premium increases when the perceived probability of default increases. But this probability increases with the total value of the debt: As the debt accumulates faster when the interest rate is higher, it naturally follows that the larger is the interest rate, the larger will be the amount owed and as a consequence, the probability of default.

Those two effects can combine themselves in an explosive vicious circle and create a self-fulfilling prophecy in which the interest rate is high since the default probability is high, but the default probability itself is high because the interest rate is high. This is the theme of a seminal contribution by Guillermo Calvo (1989) that has been refined in Ayres, Navarro, Nicolini and Teles (2015) who apply it to the recent European Sovereign Debt Crisis. [1]

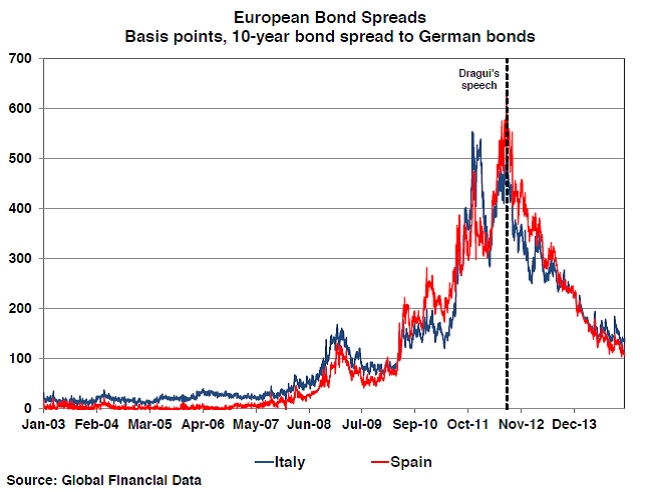

These self-fulfilling prophecies are a useful tool in analyzing the European sovereign debt crisis that started in 2010. The spreads on Italian and Spanish public debt, depicted in Figure 1, very close to zero since the introduction of the euro till 2008 and below 1% by 2010, went all the way up to exceed 5% by the summer of 2012. At those rates, the fiscal effort to service the debt is gigantic, so it is hard to believe that a chain of defaults would not have quickly followed.

What changed between 2010 and 2012? Not much. In the paper we show that the large and abrupt movements in interest rates that are observed in sovereign debt crises, seemingly unrelated to such drastic movements in fundamentals can be the result of a perverse interaction between expectations of default and interest rates faced by troubled countries.

Figure 1

Are there conditions that make these self-fulfilling outcomes likely? We argue so in the paper. We show that with long term debt (average debt maturity for these countries is almost a decade), two factors make the probability of these bad outcomes likely: First, as we argued above, the total value of the debt; second, the prospects of a long stagnation.

The expectation of a long economic stagnation critically matters since default occurs in countries when its debt is large relative to its income, as it happens also in companies and households. Thus, an obvious way to solve a sovereign debt crisis is to grow out of them. A very heated debate has dominated European policy circles, between the ones that propose growth promoting policies on one hand and the ones that propose austerity measures on the other. A problem with the first proposal, however, is the lack of consensus on what those policies actually are: if we knew how to make economies grow, we would have done it long ago.

Was Greece over-borrowing from 1997 to 2007? With today’s newspaper, raising this question seems ludicrous. However, Greece’s output grew by 40% during that decade, while still being 65% that of Germany in 2007. How reasonable was to expect that Greece could keep that pace for another couple of decades? I think most economist believed so, given the experience of other countries joining the European Union.

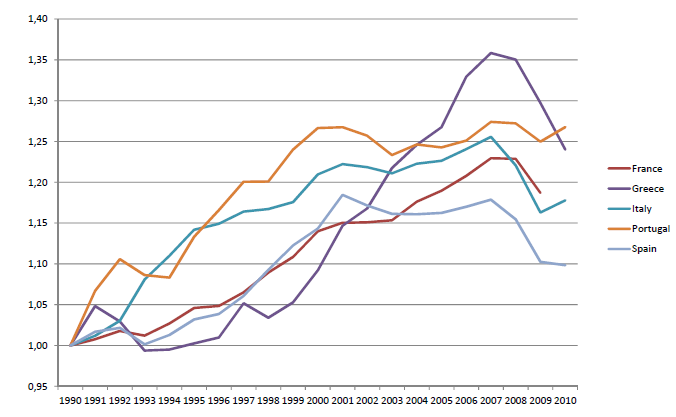

The experiences of Italy, Spain and Portugal are different from the one of Greece, but they also suggest that relative long periods of stagnation, alternating with relatively long periods of healthier growth rates. In Figure 2 we plot output per worker for Spain, Portugal, Italy,

Figure 2. Per-worker output for selected countries, 1990 = 1

Greece and France from 1990 to 2010. In each case, we set the value of 1990 equal to 1, so each plot describes the performance of each economy relative to its 1990 value. As it can be seen, France exhibits a steady growth for the overall period. Instead, Spain, Italy and Portugal exhibit a rapid growth for the first decade or so and a period of stagnation till the 2009 crisis hits. As we already discussed, Greece starts growing during the mid-nineties and grows very rapidly till 2007. This existence of long periods of “fat cows” followed by equally long periods of “thin cows” that dates back to the book of Genesis in the Bible, has actually been documented in academic papers.

Our interpretation of the European debt crisis is the following. Previous to 2008, there had been a prolonged period of relatively solid growth and low volatility in developed economies. By the first years of this century, there was little reason to believe that this would stop. When the 2007-2008 international financial crisis hit, most developed countries, convinced that the problem was a temporary lack of demand followed extremely expansionary fiscal policies, running very large deficits and increased their debt. Indeed, debt accumulation between 2009 and 2011 (3 deficits) was 72% to 108% for Portugal, 40% to 70% for Spain, and 106% to 120% for Italy. At the prevailing interest rates, there was no reason to believe default was a serious risk.

At the same time, by 2010, it became clear that what had initially been a crisis originated in the US, had expanded to Europe also and that it would be more permanent that initially thought. Thus, the two seeds, required to generate a pessimistic outcome in Europe had been planted together. Spreads started to grow till the summer of 2012, going above 5% for Italy and Spain, as depicted in Figure 1.

The Role for Policy

Is there any conceivable policy that can rule out the equilibrium driven just by pessimistic expectations of investors? As we make precise in the paper, the answer is yes. Even more, it resembles the policy adopted by the European Central Bank in September 2012, following a famous “We will do whatever it takes to save the Euro” speech by Mr Draghi, the ECB President.

In order to understand the role for policy, it is important to review the logic of the self-fulfilling outcome. According to our theory, every investor understands that by requiring a high interest rate, the market is increasing the probability that the country will default. But there is a coordination problem: the rate required by each investor depends on the rate charged by others. What is required to burst the expectations-driven equilibrium is an agent with deep pockets that can coordinate the market. The way it can do it, is to offer to buy bonds at an interest rate that is lower than the pessimistic equilibrium. In this case, the pessimistic equilibrium is ruled out and, furthermore, the large agent does not really buy any bond in equilibrium: A credible promise to buy is enough.

The outright monetary transactions (OMT) announced by the ECB in September of 2012 amounted to buying bonds of the government under the stress of the markets. The measure specified that it would buy them at “market prices”, so it did not directly address the problem of the pessimistic expectations as required by the theory. However, in the speech, Draghi did mention explicitly the need to use policy to rule out the speculative equilibrium. As it can be seen in Figure 1, where the vertical line indicates the week of the announcement, spreads went down systematically, to reach, by 2014, levels very similar to those of 2009. Interestingly, the OMT were never actually put in practice. The ECB did not need to buy any bonds: The threat to do it was enough.

The Future of the Euro

The decision of the ECB was challenged by the German Constitutional Court in January 2014, claiming that the ECB had overstepped his mandate and that the OMT opened the door for monetary financing of the deficits. At the same time, it referred some crucial points to the European Court of Justice, who, in June 2015, ruled strongly in favor of the ECB. The view of our paper is consistent with the one taken by the European Court, since ruling out a speculative equilibrium is not money financing of the deficits.

What are the prospects for the next years? In spite of the austerity policies, government debts kept on increasing in the last years and are very high. The recent elections in Portugal and Spain showed the political difficulties of maintaining the austerity policies, so it is hard to see much improvement on that front. In addition, the persistency of stagnation is so remarkable that the discussion of secular stagnations has totally replaced the analysis of the great moderation that prevailed during the first years of the XXI century. A very modest improvement in the European economy is the only, but insufficient, cause of moderate optimism. Clearly, implementing growth promoting policies would help considerably …… if we just knew which they are!

Thus, the seeds for multiplicity are still among us. How would the ECB and the German Constitutional Court react in case spreads start going up again, as they did in 2012?

[1] “Servicing the Public Debt: The Role of Expectations”, Guillermo A. Calvo, The American Economic Review, Vol. 78, No. 4 (Sep., 1988), pp. 647-661.

Working Paper 723, “Sovereign Default: The Role of Expectations”, by Joao Luiz Ayres, Gaston Navarro, Juan Pablo Nicolini and Pedro Teles.

See also Lorenzoni and Werning, “Slow moving debt crisis”, Working Paper NBER (2013).